Photo by Mark Saxby on Unsplash

Questions that tap into our mortality, our pain, our selfishness, our basic needs, questions that arise from the immeasurable darkness, light, or mystery of our lives, require more than Answerization. They require our suffering, steadfastness, silent yearning, and deepest faith. (67)

I like to keep a slow book in the stack of my morning reading. These are books that reward patient reading and the goal with them should never be to get to the end. In fact some slow books, like Annie Dillard’s Holy the Firm, inspire you to just turn back to the front and start all over again. They lie somewhere in the netherworld between poetry and prose, not quite intelligible as orthodoxy but conversant with it from a respectful distance, and overwhelmed by the spiritual enormity of the natural world.

David James Duncan might speak for my pantheon of slow book authors when he says:

I feel in my native heart and bones, first of all, that most of us drastically underestimate–with tragic results for our fish, forests, rivers, wildlife, and greater selves–just how primitive we still are: how basic we are, despite our modernity; how dependent we are on the company of native plants, animals, earth, water, air. And the second thing I feel we underestimate–again with tragic results–is how spiritually alive and capable we are. (106)

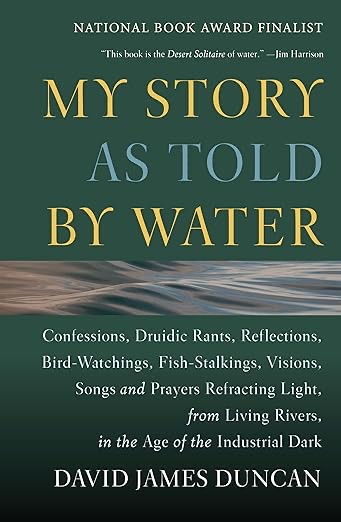

I recently finished my second tour with Duncan’s 2001 memoir My Story as Told By Water: Confessions, Druidic Rants, Reflections, Bird-Watchings, Fish Stalkings, Visions, Songs and Prayers Refracting Light, from Living Rivers, in the Age of the Industrial Dark. It’s a collection of essays that chronicle his immersion, usually literally, in the rivers of the Pacific Northwest where he grew up and still lives.

It’s safe to say no one outside Native circles has given themselves as throughly as Duncan has to trying to understand the spiritual realities of waterways and to lament the ways those ways have been diminished by the industrial age, as represented here by hydroelectric dams and mining operations. It is too little to say that he’s an inveterate fisherman. He’s part fish, part river, and part mystic.

Some of the essays move more squarely into activism. You’ll be ready to take on the Montana mining interests and the inland port of Lewiston, Idaho along with Duncan after he lays out his case. But it’s the beauty he evokes with his language and images that endures. He wants to take you deeper into the woods to find a deeper self than you knew you had. As his friend Henry Bugbee says, “The more we experience things in depth, the more we participate in a mystery intelligible to us only as such…Our true home is wilderness, even the world of every day.” (81)

I recommend a slow walk through the world with a guide like Duncan. Even as you see the heart-breaking devastation of where we are, you’ll be awakened again to wonder. And wonder, Duncan says, “is my second favorite condition to be in, after love, and I sometimes wonder whether there is a difference; maybe love is just wonder aimed at a beloved.” (88)

Some other slow books reviewed here on Heartlands:

Holy is the Firm by Annie Dillard

One Long River of Song by Brian Doyle

He Held Radical Light by Christian Wiman

This Day: Collected & New Sabbath Poems by Wendell Berry

Leave a comment