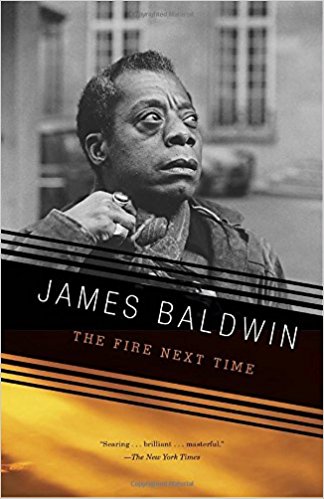

James Baldwin is having a moment, 30 years after his death. First, Ta-Nehasi Coates’ Between the World and Me, a book that drew its inspiration from Baldwin’s 1963 book The Fire Next Time, topped The New York Times’ bestsellers list. Then, a documentary about Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, was nominated for an Academy Award. It was time for me to see what the fuss was about.

The Fire Next Time is a brief, searing read. In it, Baldwin tells his own life story as an African-American man growing up in mid-century Harlem within the larger narrative of race in America. At times angry and disillusioned, it also works below the surface of racial tensions to come up with a surprising definition of love. “Love is so desperately sought and so cunningly avoided,” Baldwin says. “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” But until America, and particularly white America, comes to see itself as it really is and not as it imagines itself to be, love will be perverted into antipathy and fear.

The Fire Next Time is a brief, searing read. In it, Baldwin tells his own life story as an African-American man growing up in mid-century Harlem within the larger narrative of race in America. At times angry and disillusioned, it also works below the surface of racial tensions to come up with a surprising definition of love. “Love is so desperately sought and so cunningly avoided,” Baldwin says. “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” But until America, and particularly white America, comes to see itself as it really is and not as it imagines itself to be, love will be perverted into antipathy and fear.

“Love is so desperately sought and so cunningly avoided,” Baldwin says. “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.”

Baldwin sees the danger of the myth of innocence. In imagining that we are a color-blind society with a heroic narrative of advancing civilization, we fail to see how the ripples, the peoples!, who trouble that narrative would allow us to be more honest, more open to new frontiers. “What it comes to is that if we, who can scarcely be considered a white nation, persist in thinking of ourselves as one, we condemn ourselves, with the truly white nations, to sterility and decay, whereas if we could accept ourselves as we are, we might being new life to the Western achievements, and transform them.”

I find this book as fresh and relevant as Coates’ book, even though it is more than a half-century old. Perhaps because it seems so clear that we are just as incapable of grappling with race as we ever have been. In fact, the lines between us have hardened between those who see race as a pretext for liberal policies and those who see it’s avoidance as evidence of white nationalism.

Racism, like air, isn’t something Americans have the luxury to avoid. It just is. And like every manifestation of Sin, it has its claws in us from the time we are born. To spend vital energy denying its existence or continuing impact is to whistle in the wind. One might as well deny the fact of death, which is what Baldwin says that white Americans do.

Racism, like air, isn’t something Americans have the luxury to avoid. It just is. And like every manifestation of Sin, it has its claws in us from the time we are born.

We are prone to simple narratives in these days. Our summer blockbuster plot lines boil down to a cataclysmic confrontation with personified evil overcome by a hero, if not good, at least justified. We are drawn to leaders with simple answers – walls, guns, and jails.

But the church, which Baldwin found so energizing and ultimately disappointing, is nonetheless the custodian of a language of faith that offers something deeper. Within the story of God and ourselves in the Bible is a Love that refuses to credit any of the easy lies we tell ourselves. In the light of the cross, we can have no illusions that there is an innocent history.

We are chained by forces that resist God’s work of mercy and redemption. We are incapable of seeing how truly distorted our lives become. It takes a God incarnate in the world and on a cross to “deliver us from slavery to sin and death,” as the United Methodist communion liturgy has it.

Baldwin’s writing is suffused with the language of the church. It lends him an urgency for the time we face. To wit, his closing line: “If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!”

4 responses to “James Baldwin’s Moment and the Danger of Racial Innocence”

I just helped lead a class in Christena Cleveland’s “Disunity in Christ: The Hidden Forces That Keep Us Apart.” Lots of insight into why we interact the way we do…and offers ways toward change.

LikeLike

[…] The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin […]

LikeLike

[…] The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin […]

LikeLike

[…] reading, but what they describe is degradation and it’s going to be no less offensive. Put James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time on the list and there will still be squirming in the […]

LikeLike