Is there reason, as a historian, to be an optimist? Edward Ayers, among other things the co-host of the BackStory podcast and radio program, narrates a troubled chapter of American history in his latest book, The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War and Emancipation in the Heart of America. In the first two segments of this interview we have talked about vicious political climates and racialized narratives. But here, my former professor talks about the pendulum of history and Confederate monuments, something he’s been doing a lot of thinking about in his multiple roles:

So the grand theory of history here behind what you’re doing—-you’re saying there are these big counter-forces at work during this period. If the South hadn’t seceded, emancipation wouldn’t have happened. If the South hadn’t resisted civil rights for blacks, there wouldn’t have been voting rights and office holding for blacks. If Northern Democrats hadn’t provided cover for Andrew Johnson, the Radical Republicans wouldn’t have pushed so hard. Is that how history works in America? Not through compromise but through the opposition of grand forces?

It seems that way, doesn’t it? That’s one reason I think that we’re watching the foundations being laid right now for a new Progressive Era. I think that the opposition to Trump is going to be a major force over the next 15 or 20 years. That may be wishful thinking.

I would say that, partly because of the two party system, American history does seem to move like a pendulum rather than like an arrow. One set of accomplishments cannot be taken as a [common] accomplishment; they are taken as the embodiment of a partisan initiative. You certainly see this today in the [US retreat from the Iran deal], for no particular reason other than the predecessor did it and the current president’s undoing it.

I’ve not gotten any criticisms from anything [in my argument] yet, really. I’ve just gotten some grudging comments from people who aren’t really in sympathy with this whole kind of social history/inclusive approach. If you’re gonna criticize it, then the implicit argument here is that this diminishes the intentionality of the Republicans and of Abraham Lincoln. I don’t mean for it to do that, but that would be the criticism. The argument is that the Republicans knew all along they wanted to end slavery. That’s why they created the party. They did whatever it took along the way to do it, and then they did it. And they instituted as much Reconstruction as they could. The flip side of that is that the white South resisted every step along the way and won a large part of what they wanted, which is local control.

So I’m trying to put the two things in interplay and showing that neither of those stories —either the triumphalist one or the defeatist one—is true, but rather that each side is making the other.

These are what we might think of as dark matter. We now know the dark matter accounts for most of what’s in the universe. You can’t see it but it has gravitational effects. The Northern Democrats and the African-American people in the South and white Southerners are the dark matter that moves this great national story in ways that we can’t understand otherwise. I don’t know that it’s a grand theory as much as it is trying to explain all the orbital irregularities that we see in the story.

And if we don’t understand what the Republicans were up against, then we can’t understand really the depth of what they accomplished. I think it’s what’s surprising to people about this: I’m not following any traditional rhetoric about this of celebration or of condemnation. I’m just saying we put everybody in the screen…we put everybody in the same frame and then we see they’re making each other’s history.

I said in my Lincoln Prize address that to only look at one party or one side is like trying to understand a battle by only looking at the maneuvers of one army. That’s the basic idea of this book: we can’t understand any part without at least trying to see how all the parts fit together.

I always think of you as an optimist about the course of history. Do you feel like an optimist?

Yeah, I do actually. I think what this story shows us is that things that are far worse than we can imagine can happen and that things that are far better than we can imagine can happen too. The capacity for both swings of the pendulum are with us all the time. History has these capacities that can be tapped by people of vision and good will and ability and those reservoirs are all around us all the time.

Having watched the Civil Rights movement in my own life as a child, and to see everything suddenly change reveals to me that people of good will can make remarkable things happen. It seemed impossible at the time. I think that can happen again.

But we can also see that reservoirs of hatred and mistrust are always there, as well. I think it’s useful to know that we have to be careful that we don’t talk ourselves into the Civil War the way Americans did. On the other hand. that we need to be determined to make the most of the reservoirs and possibilities that we do have, too.

One of the things that seems to resonate between those times and these for me is this idea of how shame plays a role in the dialogue. In the Reconstruction Era, you say that the South was willing to admit defeat and the end of slavery and the Confederacy, but that the Republicans wanted more. They wanted repentance and confession of some kind of moral error. How did that dynamic play out, and are we seeing some of the same sort of language in our political life today?

Yeah, I’ll be curious to see if my fellow historians believe this. This is another kind of dangerous argument because it suggests that the Republicans were perhaps self-righteous and made problems that they didn’t need to make, which is the way that Reconstruction has been understood. These guys were fanatics, right? [is how the argument goes].

I guess it’s understandable to me why people who had tried to destroy the United States would be held accountable for what they had done. I think I’m the first one to actually locate that word ‘rebellism.’ That’s a great word. [The Republicans] recognize that the reality is that if they don’t kill that attitude, then whatever political events happen, that’s going to come back. All that to say that it’s an entirely legitimate thing that the Republicans want. It’s also probably unrealistic.

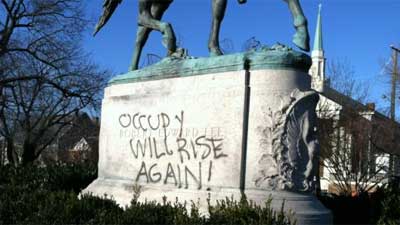

A lot of Confederate monuments were testimony to the fact that they were not going to give up their ‘rebellism.’ They were never going to admit they’d been morally wrong. They were willing to admit that they’d made a mistake strategically in giving away slavery for political independence, but they were never willing to admit that it was illegal or that it was wrong in the eyes of God.

A lot of Confederate monuments were testimony to the fact that they were not going to give up their ‘rebellism.’ They were never going to admit they’d been morally wrong. They were willing to admit that they’d made a mistake strategically in giving away slavery for political independence, but they were never willing to admit that it was illegal or that it was wrong in the eyes of God.

You see those quotes in the [Southern] papers even as the Confederacy is dying that say, “We feel that we had vindication from God to do this.” Volume One [Ayer’s book, In the Presence of Mine Enemies] is all built around the 23rd Psalm. That’s one of the most striking changes in the first part of the war is the way that the Confederacy recruits the Deity. They celebrate Lee and Jackson as particularly Christian soldiers.

If they didn’t have that…if they didn’t believe they were fighting for exactly the same ideals that the United States had been built upon…they could not possibly have waged this rebellion if they did not share the faith in this ideology with the North. They would not have been able to have changed people’s minds in a matter of weeks that something that you had opposed for years—secession—was now an essential act and that if you do it you are morally superior. If you don’t really have the larger religious framing of that it doesn’t happen.

So that’s another reason that the white South doesn’t change its mind—the idea of “We’ll be tried by adversity.” They have a script for that. They understand, “This doesn’t mean we’re wrong; it could mean that this is a trial to see how we bear it.” That helps give them a resolution that they would not have had otherwise.

In your description of the people of Staunton moving the bodies from the battlefield to the cemetery, the Lost Cause narrative is already there, which is something that I think of as developing later, once the Confederate memoirs start coming out.

Here’s another place where I’m kind of doing something dangerous. That makes the Lost Cause look more plausible. It makes you understand that it’s not just a new word for white supremacy. These were your sons that you’re burying and then reburying.

The whole idea for everything I ever do is: we’re not gonna understand if we don’t try to see it through the eyes of the people who were enacting it. We’re not going to understand the Lost Cause if we don’t understand the real grief that motivated it. The trick there is to see that grief can be wrapped in other kinds of purposes as well. That’s the tricky thing.

We have a meeting here tonight in Richmond about the Monument Avenue Commission. We’re coming to a conclusion of that and I think people are slowly coming to see that the knee-jerk formulations—“It’s just history and you can’t change it” or “[The people who erected the Confederate monuments] didn’t mean anything politically by it” are not true. On the other hand, for people who are standing on the other side [it’s important to understand that] the people who are building these things are still grieving for sons and fathers they lost. It’s also important to understand this if we’re gonna move forward—what all the people who put the monuments up originally meant by them.

Thanks for the book. I hope it gets a broad readership. It should.

Yeah, you know, getting a Lincoln Prize…all my friends here who are not in the history biz were most impressed that I beat Ron Chernow [author of Alexander Hamilton] and winning the Avery Prize from the Organization of American Historians. But I think that our impact comes from classrooms for the next twenty years. I hope, that’s where the impact comes from—people actually have a chance to think about it a little bit rather than just reading the book then moving on.

So there’s not an Alexander H.H. Stuart musical coming out?

They did actually do a stage dramatization of it at the Black History Museum in Richmond based on words of four characters: two white, two black, two men, two women. It was very powerful. Just the words and a few of mine along the way. So it would make a great movie or a great miniseries. So if you could make that happen I would appreciate it

We’ll get Lin-Manuel Miranda on it and see what he can do with it.

That’d be great.

One response to “Musicals, Monuments, and Historical Optimism: The Ed Ayers Interview concludes”

[…] Click on this link for Segment 3, “Musicals, Monuments, and Historical Optimism.” […]

LikeLike